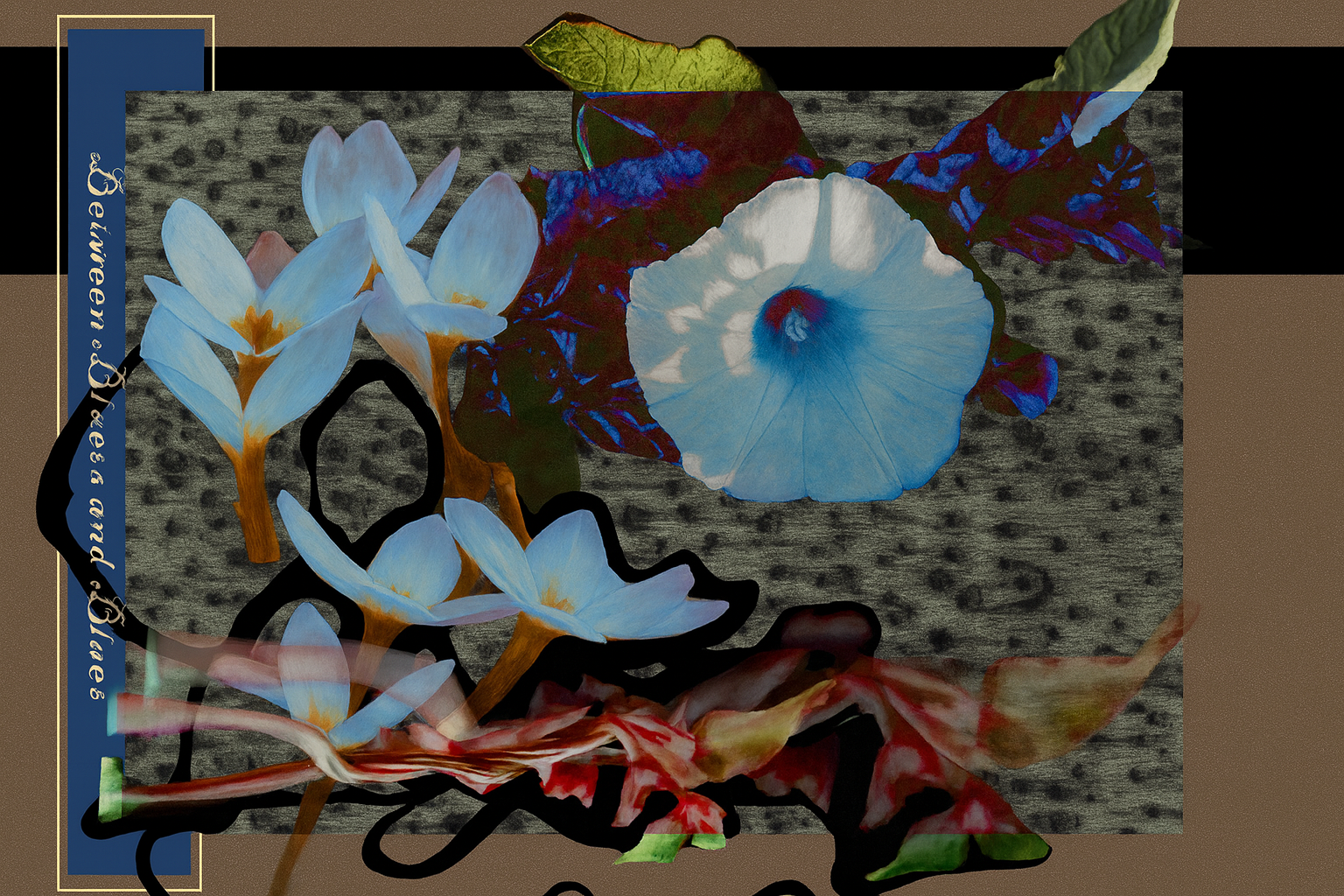

Between Bluets and Bindweed

Afterwards, you imagined lying among low-growing gentians and bluets, monkshood and mayapple, the mottled shade of anything green still close to the earth because sympathy cards were as useless as cut gladiola splayed on top of a coffin.

You believed you needed to learn that grief must be grounded and slow, that most tendrils of sorrow could be traced to moments that began long before his end and that such moments could be held until they softened.

This, you thought, is how your future might someday emerge,

which of course has nothing to do with how a plant thrives.

Ailing bindweed, for example, have back-up plans. If seeds don’t germinate, each blossom can drop another hundred. If shade stymies growth, their slender vines will strangle nearby phlox as they climb to bask up high in the unblocked light. They’re an invasive species. They take what they need from others.

You wondered whether the will to go on living would require such a choice.

Later, walking the trails, you study the bluets that avoid full sun to bloom in the shade of the forest floor

and then the bindweed’s reminder of how ruthless a survivor can become.

Some days now you choose tenderness. Other days, tenacity.

This is why decisions about where to go and what to do next still exhaust you. You can’t see yet that you’re reducing choices to either/or; if this, not that and nothing in between where almost everything worthwhile begins.

This, you’re sure, is good advice which, like all advice,

has nothing to do with how a heart heals.

Barbara Hurd is the author of six collections of essays about the natural world. Read more.