Why, Plants?

Three months, eight advisors, and countless conversations later: our project, nourished by the perspectives of many disciplines, has put down deep roots. Deep enough, we believe, to both germinate into the installation we were commissioned for and support mycelially-expanding collaborations to become more than we ever imagined.

“So, why plants?” asked one advisor, photobiologist Dr. Ronald Pierik, when discussing our chosen pathway to reconnect with the natural world. “I mean, animals would obviously be easier to establish communication with, and there are plenty of fascinating species of fungi, microbes, bacteria, and the like that comprise our natural ecosystems.”

Why plants? It was a good question and one that we hadn’t deeply asked ourselves. But when we did ask, reasons abounded. Plants act as symbols of the natural world, ambassadors even. When humans picture nature, we intuitively picture green things: the great photosynthesizers. We cling to them, bring them indoors as “houseplants” to act as a salve for our lungs and our minds. No matter how alien they may feel to us, we sense that our lives depend on theirs. Because they do: plants are not only symbols of nature -- they create nature. They create the oxygen in the air we breathe, they gather moist clouds to them and release the rain that hydrates our bodies, they become the soil that becomes our food that becomes part of us (just as we, at the ends of our lives, become them). As another advisor, multispecies anthropologist Dr. Natasha Myers, so beautifully puts it: “We are of the plants.”

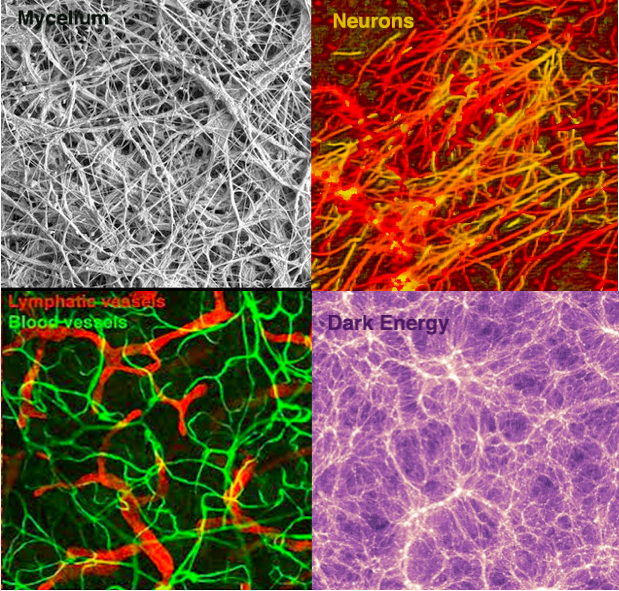

But simply because we are of plants and plants are of us does not mean plants are us. This sounds obvious, but our teachers - from scientific, ethical, ecofeminist, indigenous, and artistic backgrounds, alike - have warned us of trying to make people care about plants by emphasizing our similarities. Yes, we share a basic common ground - electrical potentials for communication - but the direct similarities stop there. Indeed, it’s our differences that we should understand and celebrate -- differences that make us not superior or inferior species, but complementary members of a community. Take our interactions with light. Humans and plants both perceive and respond to blue light waves, but humans use them to see images while plants use them to create food. We both perceive and respond to infrared light waves, as well, but we sense them as heat while plants use them to sense how far away their neighbors are and thus decide whether to grow taller or bushier! The list goes on. Knowing this, we’ve struggled to find a simple narrative for our project that everyone can understand, regardless of previous knowledge, while still portraying phyto-sentience in all its complexity and differentiation. It’s less about making people care than about creating the conditions for us to listen to plants’ stories or teachings. In other words, it’s not, “why plants?” but “why, plants?”

Listening to plants is a more political business than we first imagined. Dr. Myers also brought us face-to-face with some uncomfortable thoughts: that the scientific method often depends on treating the sentient subject as inanimate object in order to extract a “valid” signal, that truly relating to other beings is an embodied practice that no technology can fully replace, and that a passing communicative encounter can never be deeply transformative when our conversation partner lives on a timescale up to 1000x slower than ours. Which seemed problematic, since our project employs both scientific knowledge and technological mediation, as well as trying to be accessible to the passerby - meeting them where they’re at with minimal effort. So, we dug deeper to understand our role in the tremendous task of bridging scientific and other ways of knowing - including the indigenous*, the intuitive, and the artistic.

Speaking to our many plant science advisors, we were dismayed to learn that most plant electrophysiology research has historically depended on wounding the plant. With research dollars pouring in from the agricultural industry for stress resistance studies, researchers were incentivized to focus on plants’ defense signalling capacities - most easily induced through biotic (insect munchings) or abiotic (mechanical wounding) damages. Our team, however, is interested in electrical communication in “happy” plants - what psychologists would refer to as “healthy normals.” Pioneering plant electrophysiologist Dr. Ted Farmer helped us identify examples of action potentials produced in these “happy” plants during watering, nutrient exchange with symbiotic organisms, pollination, and gentle touches or brushes (plant massages, anyone?). “There appear to be many more electrical activities produced by healthy plants as they grow,” he mused. “What a pity we don’t give their biology the attention they deserve.” And then: “But you know, wounding is itself a healthy part of plant growth. Just as humans need to experience some stress in order to develop into self-sufficient adults, a tree cannot grow tall and strong if it’s never exposed to strong winds.”

Groundbreaking research by Dr. Simon Gilroy's lab demonstrates how plants send calcium-mediated electrical signals between leaves when under attack - usually resulting in the plant releasing defense chemicals that make them less tasty!

Clearly, opening the door to an ethics of sentient plants produces more questions than answers. We found ourselves searching for answers beyond the scientific, from other ways of knowing. We turned to Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass. As a botanist, poet, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, she works to unite scientific, artistic, and indigenous ways of knowing the natural world. Science, she writes, polishes the arts of seeing and deep attention, while indigenous knowledge springs from the arts of listening and language. Science is for learning about plants; indigenous knowledge is for learning from plants. And both ways are important, both are better.

Reflecting on those words, we begin to understand that our seemingly small project holds even greater importance than we knew. With our interactive installation, we had inadvertently chosen to create an experience that ferries people from the comfortable yet rigid entry point of scientific knowledge - learning about the incredible complex sentience of plants and our shared basic tools for engaging with the world - to the lesser known shores of intuitive ways of knowing - learning from plants through both direct communication and a foray into the “plant’s-eye-view” of the world. All of this, this whole passage, we are making possible through art and technology. And, moreover, we are discovering the opportunity to enrich our understanding of how we, as a human species, can live sustainably with each other on this planet. So, can we prove that science and technology need not be enemies of artistic, emotional, and intuitive ways of knowing, but collaborators? That no method is more simplistic than the other, but that together they are simply more?

We do not approach the scientific signal of electrical potentials as ends in and of themselves, but as the basis for artwork that imaginatively relays the plants’ own expression and builds a felt relationship between species. We have decided that creating a single mobile interaction tool at this stage would overly constrain the potential learnings of phyto-dialogue: we must first create a full installational performance in which plants are the main characters. We have realized that our website, which was originally meant to be a disseminator of information about our project, actually has a larger responsibility to facilitate the bridge between disciplines: a globally accessible space to invite listening to and interpretation of the “raw plant experience” we gather through our scientific, technological, and artistic research methods. We hope that our project will be not the end, but the beginning of our audience’s relationship with plants. And we hope that they will emerge, yes, with a new level of literal understanding of how plants work, but also with a sense of admiration, kinship, and gratitude for these green creators.

Finally, there is the question of reciprocity. In experiments with human subjects, we always do our best to ensure their participation brings mutual benefit, whether through access to a potentially life-saving drug in a clinical trial or simply learning something new about their minds from a psychology researcher. How will our Brain-Plant Interface project be as beneficial to the plants as to the humans? Looking back at our overarching project intention, we find the key: we seek to restore humans’ sense of belonging within our natural ecosystems, in hopes of activating greater care and action for this earth. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s words speak to us here, too. She writes: “It was through actions of reciprocity, the give and take with the land, that the original immigrants became indigenous...To become naturalized is to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do. Live by precepts of the Honorable Harvest -- to take only what is given, to use it well, to be grateful for the gift, and to reciprocate the gift.” Showing gratitude for plants can come in many forms. In words, drawings, poems, songs, or dances, or in more practical forms like planting, tending, cooking, and, yes, fertilizing. What gift will each audience member of our installation leave behind in thanks? It is up to each of us.

Until next time,

Anna, Fernando & Skip

+ Fernanda & Teresa, who also joined the project!

*Note: Indigenous ways of knowing refer to the canon of knowledge, practices & philosophies developed by Indigenous Peoples in sustaining mutually beneficial relationships with the natural world. By referencing the term, we aspire to carve out as great an intentional space for its teachings as we do for science.